Prezydent Cagliari: Mam nadzieje, że Barella zostanie

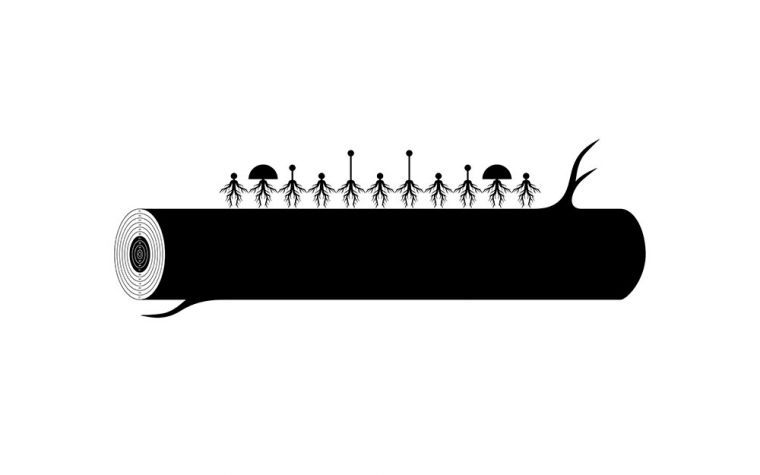

default, Back to Your Roots: An Interview with the Creators of MYCOsystem, 'MYCOsystem' by Małgorzata Gurowska, photo: AMI press materials, center, myco_animacja_052.jpg

#design #Culture.pl Interviews

In 2019, the Triennale Milano wants to save humanity. The theme of this year’s grand event, which promotes modern design and architecture every three years, is ‘Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival.’ The artists representing Poland are bringing a rather earthy take to Milan, with a work that centres around fungi.

Representing Poland during the 22nd Milano Trienniale is the exhibition MYCOsystem, created by curator Agata Szydłowska, visual artist Małgorzata Gurowska and architect Maciej Siuda. Before they headed to the opening on 1st March 2019, the team explained to Culture.pl’s Anna Cymer why their exhibition explores the very ground beneath our feet.

Agata Szydłowska

Agata Szydłowska: This year’s theme obviously has a focus on human beings, but in our project, we also interpret it in the broader context of the relationships between homo sapiens and other species living on planet Earth. For us, the theme proposed by the curator of the 2019 Trienniale, Paola Antonelli, is a call for recreating the broken ties between humans and other species and for a better understanding of biological and ecological processes, which can serve as an inspiration and point of reference for designers.

Anna Cymer: Your project is extraordinary. It doesn't include works of art, objects or designs. Please tell us about the concept behind it all.

AS: Biodesign is an important element of contemporary design. It’s all about searching for materials and solutions created together with other species in order to create environmentally-friendly products. It’s a very interesting and important trend, but if we take a look at all the processes occurring in the environment, it turns out that natural materials, such as raw wood, will always be the best biodegradable option. And it’s all thanks to fungi. This is why our work concentrates on the realm of living organisms.

If we analyse materials from a cross-species perspective, we notice that fungi appear at both the beginning and at the end of the existence of living things. They enter into symbiotic relationships with 90% of plants; in scientific language, we would call it mycorrhiza. The relationship between fungi and trees is a great example of interspecies co-operation. Without fungi, trees wouldn’t grow, decompose or undergo biodegradation. Few know about this interdependence and we really wanted to describe it in greater detail.

Design Divas: The Women Who Rule Polish Design

AC: How did you convey these thoughts and knowledge in the form of an exhibition? Your concept had to be comprehensible to a wide international audience.

AS: We had a simple idea for the exhibition. We didn’t come up with new ideas, but instead we decided to understand and convey knowledge about the ancient ways of nature, the natural process of decomposition from which humans have long separated themselves with the help of various chemicals. We wanted to show our respect and understanding towards natural processes, so that we all could finally learn to co-exist with nature.

Hence this exhibition, which is a source of knowledge and information conveyed in an understandable and beautiful form.

Maciej Siuda: Contemporary designers concentrate on inventing new objects, forms and materials. They forget about the natural options, which should in fact be immensely dear to our hearts. We believe that describing this forgotten natural phenomenon might become an inspiration for other people to include it in their work.

We’ve conveyed our message using well-known and accessible methods, the smallest of which is iconography and the largest is architectural installation.

Małgorzata Gurowska: It’s worth mentioning that our working methods were inspired by how fungi co-operate with other organisms [laughter]. We decided that each of us would represent a participant in the process – one of us was a tree, the other one was a fungus and the third one was a human being. We were all interconnected. This exhibition was a process that we finished thanks to co-operation without the traditional division into curators and artists. We all concentrated on our main fields of competences and abilities, but our partnership was key. Fungi, the champions of co-operation, inspired us to test new democratic methods of creating exhibitions, leaving behind rigid divisions and traditional roles.

Maciej Siuda

AC: Indeed, your exhibition incorporates architecture, video, music, graphics and knowledge.

MS: The wooden installation, the huge shape filling the entire space of the Polish pavilion, is an attempt to present the world of nature and what grows on the forest floor. It’s a wooden platform, which stands at 45cm at its lowest point and rises to nearly three metres. Its shape resembles a lifted carpet and viewers can see what’s underneath. It was designed against any architectural rules: light objects are at the bottom, while the heavy ones are at the top. By raising the platform, we reveal thin fragments of roots and small elements appearing in soil beneath.

It’s a large construction that encourages you to get up close. We didn’t want to create an object for viewing, but a structure which absorbs the audience and allows for interaction. And this wooden installation is not only an architectural project, but also the basis for a drawing, which is a source of information closely linked to infographics and videos.

MG: At first glance, the drawing is abstract, but in fact none of the thousands of holes in the work is accidental. The work combines micro- and macroscale. Light filters through the holes, resembling the night sky with its many constellations. In fact, the microscopic image of the mycelium looks just like the sky, as does wood destroyed by insects, such as woodworms, which carry fungi to the inner layers of the trunk when boring into a sick or weakened tree. We tell the story of creatures, which, unlike humans, don’t take all the wood for themselves, but instead they share it with fungi. This is how the cycle goes – the fungi eat the wood and fertilise the soil, so that other plants can grow.

Małgorzata Gurowska

AS: The infographics on the wall are less abstract. We wanted to convey the information we gathered and the idea of MYKOsystem in the most accessible way. We also wanted to be honest about the environmental costs of the whole project.

MG: I constructed statements using signs, which perform a function analogous to the one of letters. I use these ideograms to build words, entire sentences, tell different stories. These icons have their own specific meanings and appear in different configurations. I tell stories about both the co-operation of fungi and trees and the utilisation of waste from the lumber industry. The exhibition also includes a five-metre-high infographic depicting an entire tree and the accompanying mushrooms. Next to them, there is a scale showing the height. In this way, we wanted to encourage the audience to look at their relationships with other species. In this simple way, viewers will not only be able to cast doubt on the position of homo sapiens as the rulers of the world, but they will also notice all the tiny elements of the environment that they don't usually see.

AS: Our exhibition has great educational value. We show phenomena, describing relationships between species and the natural processes linked with industry.

MG: It’s a peculiar kind of exhibition, and we really wanted it to look beautiful. We wanted it to be charming and pleasant for the audience.

AS: Music composed by Joanna Halszka Sokołowska plays an important role in the work, so does light and the smell of natural wood. At the same time though, we wanted to change the way people think about materials used to create various objects. MYKOsystem is broad and ambitious, but also a utopian project that aims at reinventing the design process: from logging, through industry, design, to utilisation. Creating the exhibition itself was a great field of practice for such a process.

'MYKOsystem' by Małgorzata Gurowska, photo: AMI press materials7 Decades of Polish Pavilions: International Exhibitions In The Face Of Politics, Trends & Shortages

'MYKOsystem' by Małgorzata Gurowska, photo: AMI press materials7 Decades of Polish Pavilions: International Exhibitions In The Face Of Politics, Trends & Shortages

AC: Was there something that surprised you or turned out to be difficult?

MS: The construction of the platform itself was a huge challenge. Its design allows for demolition and biodegradation or reassembly. We really wanted it to be built in the most natural way, without any artificial elements. It wasn’t easy at all!

AS: It would seem that there’s nothing simpler than an object made of raw, natural wood and a couple of paper prints. It turned out that there were lots of technological, constructional and legal restrictions hindering this method of creation. We had to constantly negotiate with the construction team and adapt to surprising fire safety rules, bureaucratic regulations, EU security rules, and so on. We learned that the most natural solutions require negotiation and compromise. This applies to both our wooden installation and the printed graphic works.

MG: We had to explain to the printers and bookbinders why we wanted the publication accompanying the exhibition to be sewn, not glued. They all wanted to use glue, as books bound this way are much more durable. But we didn’t care about durability! It’s some kind of illusion, because things get broken all the time and no one buys things to last a lifetime.

AS: Creating edible objects for our decomposers – fungi – was an important and educational aspect of our work. It turned out that dozens of tiny barriers separate us from nature, such as forcing us to use chemical protection.

AC: Ecology and awareness of natural processes and environmentally-friendly production are extremely strong trends in contemporary architecture and design.

AS: We really need a new way of thinking about architecture and design. We need to move away from the 20th-century concept in which a project, an object or a building, is the final product, fully controlled by people. Designers and architects have become accustomed to the fact that their work is immutable, protected against aging and degradation, and that it remains in its original form – it doesn’t rot, distort or change its colour.

Today, we know that the exploitation of our planet has gone too far and that we must do everything to protect it. It’s necessary that we change our way of thinking about design; we must stop treating our achievements as final and immutable. We must focus on the process and interdependencies and to enter into the cycle of natural processes. We must also accept the fact that objects are temporary. We should all be open to the fact that the objects that serve us will be subject to biological degradation; that we will lose control over them – for the benefit of the environment, nature and the planet. In our exhibition, we wonder what would happen if we renounced total control over the surrounding materials and gave them back to nature and its processes of creation and decay.

Interview conducted in Polish, Feb 2019; translated by AJ, Feb 2019

VeryGraphic: Polish Designers of the 20th Century triennale di milano agata szydłowska Maciej Siuda Małgorzata Gurowska contemporary polish design

Komentarze